Cultura

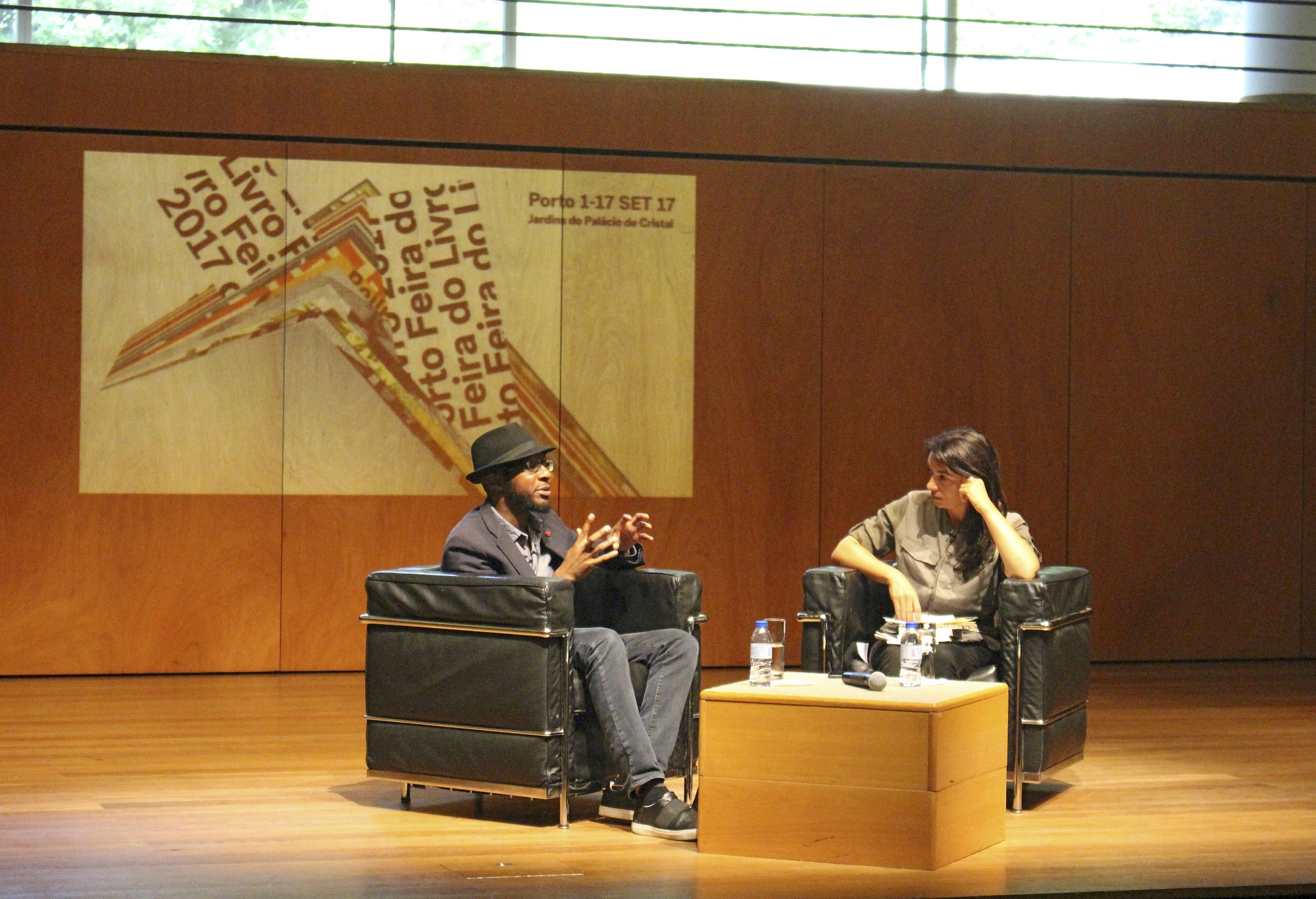

DEBATE ON NEW PATHS OF AFRICAN LITERATURE WITH TEJU COLE

Teju Cole is probably best known for his literary work: his novels Open City (2012) and Every Day is For The Thief (2007) have been translated to Portuguese. However, his work extends far beyond that: he is a Photography critic for The New York Times and a photographer, an art historian and a music lover, a political activist and a soccer fan. More importantly, he turned out to be a bright, reasonable and charming speaker, who constantly interacted with audience and had patience to deconstruct and to answer their questions.

ON AFRICAN LITERATURE

Teju Cole points out that there is no such thing as African Literature. He assures that he is not against categorization, but rather of what the categorization implies. We do not speak of European literature, not very often at least. However, the literary form of novel was born in Europe, which makes him and any other novelist from around the world practice a European literary form.

ON HOW HE DEFINES HIMSELF AND HIS WORK

He is a writer who is from the African Continent, from Nigeria, from the city of Lagos, yet he has also spent a large portion of his adult life in the US, and his books are about cities with lots of walking included. He says that his characters are black because he is black, just as he writes about walking because he’s never learned how to drive a car. His sensitivity is influenced by his African heritage, yet his literary influences are James Joyce and Virginia Woolf; he enjoys Brazilian music and hip-hop from the Bronx; he has travelled around the world and accumulated his own, unique experience of life. He is his country, metaphysically.

ON WHAT BEING A WRITER MEANS

Books used to be seen as conveyors of information and knowledge. We are currently living a technological and informational upsurge; one does not have read a book to learn something new anymore. People read books to be entertained, to be consoled. They want company or someone to make them laugh. But a writer goes beyond that: he is someone who can give you an idea of how you can use your freedom, beyond your cultural heritage, and what can be the dangers of such freedom.

ON INCREASED INTEREST IN NIGERIAN WRITERS

While he is a writer from Nigeria, he has had access to wide visibility among American publishing houses, a privilege many young writers do not have. No matter how much we spoke of Nigerian writers over the years, the truth is that there are still infinitely more French writers than Nigerian, while the population of Nigeria is 4 times bigger. Before the amount of Nigerian writers is proportionate with that of Western European ones, one cannot speak of upsurge in interest. Before we overcome the gap of inferiority we cannot speak of progress. The future will come and it will be black [laughs].

ON WRITING IN ENGLISH

To be living in an English speaking country is probably like being a woman who lives in the society organized according to the needs of men. It is disagreeable, but it is a reality, one accepts it. Language is a tool, as a writer one tailors it to one’s needs. Because of him, of his sensitivity and experience, English can say new things now. And if we think about it, possibly the most common language in the world is not even Chinese, it is Bad English. This is the field offered to every one of us, and it is here where we do our work.

ON AFRICAN AUTHENTICITY

Questions not what African authenticity actually is, but of what people expect him to do/demonstrate when the seek it. Have we meet a truly authentic Portuguese? Probably the not, because we are all contemporary. Cooperation, exchange and borrowing have accompanied the history of civilizations. As an example, the very debate is happening in an auditorium, which is a Greek invention. But Portuguese did not have to invent their own analog of auditorium, they borrowed it, and it became a Portuguese auditorium. Is it authentic? No, nor does it need to be: a path to equality is cosmopolitanism.

ON BEING PATRIOTIC

A patriot becomes an object who is programed on how to feel and what to accept/refuse. A citizen (which he is of two countries) on the contrary, is someone who is conscious of the freedom he has, and he exercises that freedom of thought.

ON POLITICAL ACTIVISM

To resist, to refuse the abnormality that is happening in the US and around the world does not only consist in being vocal about it. This responsibility goes beyond text, beyond literature. Decolonization is a daily task. It can be refusing to be sponsored by the government that you do not accept (like Teju Cole does), but it can also be questioning the correctness of your thoughts, it can be losing people in your own life who have gone on the racist, oppressive path, it can be motivating yourself to see the wrongdoing and not to be passive about it. It is painful that the idea of genetic inferiority of blacks has only been present in the history of our civilization for about 600 years, and yet is still painfully remnant today.

ON TEACHING CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ART

Followed-up question regarding the correctness of admitting the fallacy in the term ‘African Literature’ and utilizing a similar one for art: all University courses have to have a name, and often one needs to tag a geographical location/heritage to one. His goal is not to define what Contemporary African Art is and how it differs from other artistic production. He did not pretend to focus on African artists living in Africa, nor was he speaking exclusively of black artists. It was a chance to bring attention to Africa, to what it means to be subjected to certain painful stereotypes, to how universal, rather than cornered, artistic production of authors of African origin could be.

African topic continued with a conference Memory and Identity, or Africa in Forming of The New Portuguese Identity. Africa has been gaining recognition and interest over recent years and is, more than ever, important now. Last year in France was announced to be the year of African Art. This November, the New York PERFORMA Biennial will be dedicated to the work of African performance artists. In Portugal, this summer was celebrated with screening of the documentary I Am Not Your Negro, a film on life and work of James Baldwin. This October, Núcleo de Arte, a museum in the city of São João da Madeira, will inaugurate the exhibition on African Outsider Art, In and Out of Africa.